Yet Another Kubernetes Intro - Part 9 - Ingress, Dashboard and extras

So…it is finally time for the last installment in my introduction to Kubernetes. So far, we have gone through what it is, Pods, ReplicaSets and labels, Services, Deployments, configuration, storagestorage and namespaces and RBACnamespaces and RBAC. That is a lot or information! But wait, there is more!

Well…there isn’t a whole lot more that I think needs to be covered in an intro, but there are a couple. So in this post, I want to show you how to use something called an Ingress Controllers, how to set up a Kubernetes dashboard to get an overview of your cluster, and finally, have a quick look at some more things that you can do with kubectl, and how you can use it to manage and debug you solution.

Ingress Controllers

But first out is the Ingress Controller. An Ingress Controller is kind of like a Service on steroids. It allows you to route traffic to different pods in the cluster, kind of like a Service. However, it also knows about HTTP. So you can do your routing based on HTTP things like hosts, paths, headers and so on. This can be a really useful and flexible way to combine a microservices system into a single API for example.

In this post, I want to give you a quick intro to maybe most simple Ingress Controller out there, the nginx-ingress, which is built on…you guessed it…nginx! But before I get into how to set up the nginx-ingress, I want to mention that there are a lot of ingress options out there. Nginx it pretty labour intensive to use. It requires you to reconfigure the ingress resource whenever you need to modify the routing. Other ingress controllers, like Traeffic and Ambassador for example, allow you to configure your routing using annotations on your services instead. But that is a topic all in its own. So, to keep it simple I’m going to stick with nginx.

Installing the nginx-ingress

Kubernetes doesn’t come with any ingress controllers out of the box. Instead, you have to figure out what ingress you want to use, and install it on your own. Luckily, this is generally a piece of cake, as it often just means applying a YAML file from GitHub. And in the case of the nginx-ingress, that is just the way to do it. Just run the following command with your kubectl pointing at the correct cluster

kubectl apply -f https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubernetes/ingress-nginx/master/deploy/static/provider/cloud/deploy.yaml

This will install everything you need to get nginx-ingress support added to your cluster.

Configuring an nginx-ingress

Next, you need to configure your ingress to do some routing. However, to be able to do any form of “useful” routing, we need something to route to. So for this demo, I’m just going to quickly set up 2 pods and 2 services to use as my routing endpoints. The pods will be based on the hashicorp/http-echo image that allows us to easily create a pod that returns a predefined string. In this case, the returned strings are “PING” and “PONG”. The set up looks like this

kind: Pod

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: ping

labels:

app: ping

spec:

containers:

- name: ping

image: hashicorp/http-echo

args:

- "-text=PING"

---

kind: Pod

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: pong

labels:

app: pong

spec:

containers:

- name: pong

image: hashicorp/http-echo

args:

- "-text=PONG"

---

kind: Service

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: ping-service

spec:

selector:

app: ping

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 80

targetPort: 5678 # Default port for image

---

kind: Service

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: pong-service

spec:

selector:

app: pong

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 80

targetPort: 5678 # Default port for image

That gives us 2 pods, ping and pong, and 2 services, ping-service and pong-service. The services redirect traffic on port 80 to the containers “natural” port 5678.

Now that we have these services to route traffic to, we can set up our ingress.

Note: You want your ingress to route traffic to services, not pods. The ingress isn’t a load balancer, it is just a routing mechanism. So to get load balancing and pod fail over and so on, you still need to use a service.

To set up the required routes, we need to define an ingress resource. The way that you do that for an nginx-ingress is by creating something that looks like this

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: ping-pong-ingress

spec:

rules:

- host: kubernetes.docker.internal

http:

paths:

- path: /ping

backend:

serviceName: ping-service

servicePort: 80

- path: /pong

backend:

serviceName: pong-service

servicePort: 80

As you might be able to figure out, this creates an Ingress resource called ping-pong-ingress. It’s configured to only respond to the host kubernetes.docker.internal, which is a host name set up on nay system running Docker Desktop by default. I guess I could have used localhost as well, but I decided to use this dedicated host instead.

In the configuration, I configure 2 paths. The first one, /ping will be routed to the service ping-service on port 80, and the second one, /pong is routed to the pong-service service. A very simple routing set up for a very simple scenario. But trust me, you can have much more complex set ups as well.

Once we have the spec in place, we can apply it in our cluster

kubectl apply -f ./ping-pong-ingress.yaml

This sets up a new nginx-ingress resource in the cluster for us. This ingress binds to port 80 on the local machine when running Docker Desktop.

Warning: If you have anything running on your machine that uses port 80, this is not going to work. In my case, I have IIS installed, which hogs port 80. So to solve this, you have to stop any process that is using port 80 while you are working with Kubernetes ingresses locally.

Ok, with the ingress resource in place, you should be able to pull up your browser and verify that it works by browsing to http://kubernetes.docker.internal/ping. Or, by using curl to verify it by calling

curl http://kubernetes.docker.internal/ping

StatusCode : 200

StatusDescription : OK

Content : PING

RawContent : HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Connection: keep-alive

X-App-Name: http-echo

X-App-Version: 0.2.3

Content-Length: 5

Content-Type: text/plain; charset=utf-8

Date: Fri, 24 Apr 2020 09:55:24 GMT

Server: nginx/1.1...

Forms : {}

Headers : {[Connection, keep-alive], [X-App-Name, http-echo], [X-App-Version, 0.2.3], [Content-Length, 5]...}

Images : {}

InputFields : {}

Links : {}

ParsedHtml : mshtml.HTMLDocumentClass

RawContentLength : 5

And if you use curl http://kubernetes.docker.internal/pong you get a PONG back instead of a PING. So it seems like our ingress controller is doing its job.

Setting up a Kubernetes Dashboard

Ok, now that we know how to use a nginx-ingress, let’s move on to another thing that might be interesting to do in your new cluster. And that is to set up a dashboard that let’s you monitor your cluster using a graphical UI.

The cool thing here, is that there are already a couple of different options for K8s dashboards out there. But I’ll use the official one called…wait for it…Kubernetes Dashboard!

To install it in a cluster, we just need to run

kubectl apply -f https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubernetes/dashboard/v2.0.0/aio/deploy/recommended.yaml

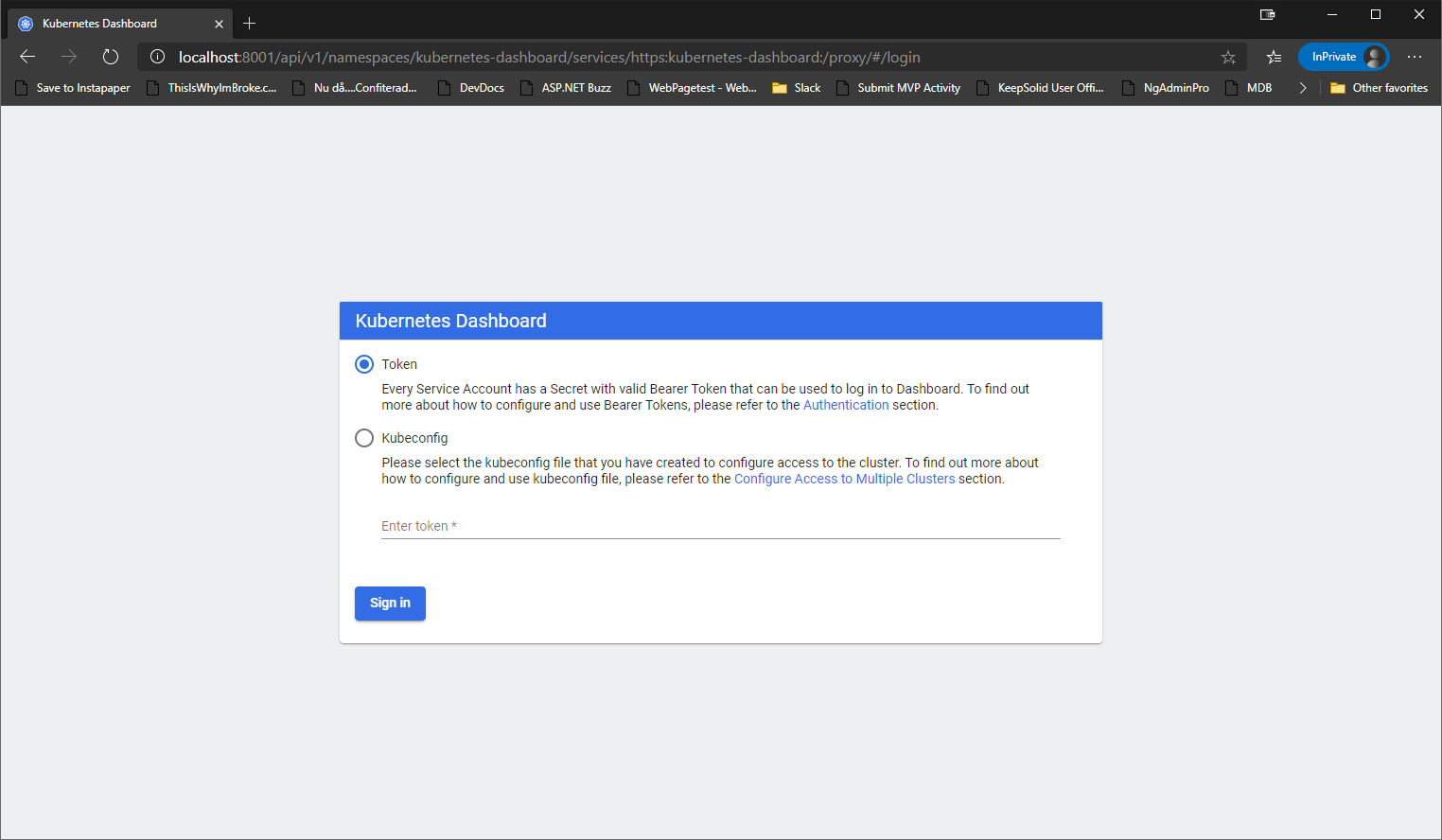

However, once you have done that, you need to figure out how to access it. This involves two problems. First of all, we need to actually reach the dashboard. And secondly, we need a way to authenticate ourselves.

Let’s start with problem 1. How do we reach the dashboard? Well, there are a couple of ways. It seems like the most commonly cited one on blog posts is to use kubectl proxy. So let’s try that first.

By running kubectl proxy, kubectl will set up port forwarding to the Kubernetes API on port 8001 on your machine. Once that is up and running, you can access the dashboard service by browsing to http://localhost:8001/api/v1/namespaces/kubernetes-dashboard/services/https:kubernetes-dashboard:/proxy/

The address being used tells the system that you want to browse to the kubernetes-dashboard service in the kubernetes-dashboard namespace, using HTTPS.

Ok…so this works…ish… But I think we can access it in a better way. But lets first focus on the 2nd problem before making the solution to problem 1 better.

Accessing the Dashboard

The second problem is authentication. The dashboard requires authentication for obvious reasons. This can be done either by supplying it with your kubectl config file, or by giving it a token. The token way is definitely preferable in my mind. But the question is how we get a token?

Well, it kind of depends. There are a built in accounts that gives you access. So you could just get the token from one of those. Or, you could set up a new ServiceAccount, and a ClusterRole binding, to get access. And since I think that is a better solution, let’s go with that instead…

To create a new service account, we can use a spec that looks like this

apiVersion: v1

kind: ServiceAccount

metadata:

name: dashboard-user

namespace: kubernetes-dashboard

This creates a new ServiceAccount called dashboard-user in the namespace kubernetes-dashboard.

Note: It needs to be in the kubernetes-dashboard namespace, as the Kubernetes Dashboard is deployed in this namespace.

Next, we need to bind a ClusterRole called cluster-admin to it. Well…honestly, you should probably lock it down a little and not just assign admin privileges for the entire cluster just to access the dashboard. But for this demo, I think it is ok…

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: ClusterRoleBinding

metadata:

name: dashboard-user

roleRef:

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

kind: ClusterRole

name: cluster-admin

subjects:

- kind: ServiceAccount

name: dashboard-user

namespace: kubernetes-dashboard

As you can see, this assigns the cluster-admin role to the dashboard-user on a cluster wide level.

Note: The token defines what you are allowed to see in the dashboard. It uses the privileges of the used account when talking to the API to generate the dashboard. So the dashboard will show whatever the user has access to. In this case, the whole shabang!

With that in place, we need to get a token. Luckily, each ServiceAccount gets a token generated on creation. So all you need is a few kubectl commands. Or you can combine them and just run this in PowerShell

kubectl -n kubernetes-dashboard describe secret $(kubectl -n kubernetes-dashboard get secret | sls dashboard-user | ForEach-Object { $_ -Split '\s+' } | Select -First 1)

The last row that this command’s output contains the token. So you need to copy that.

Warning: When you copy the token, it is very likely that your terminal has been nice enough to split it up on a couple of rows. This won’t work as there are line breaks in the copied value… So try pasting it in for example Notepad to make sure that there are no line breaks in the text. If there is, just remove them and re-copy the text without them…

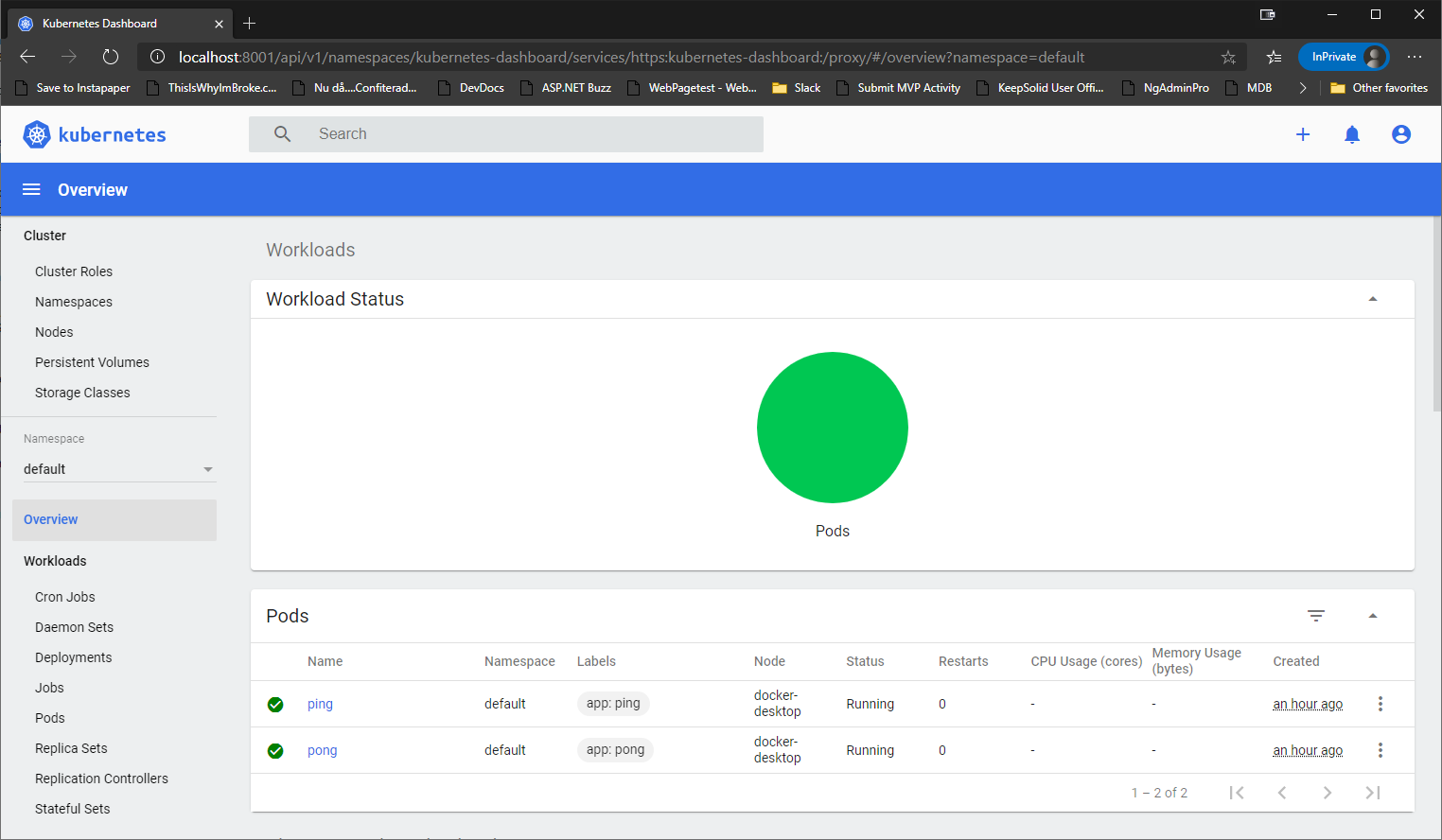

Ok, now you should be able to go back to your browser, insert the token and sign in. Once you are singed in, you will be created by something that looks like this.

I suggest you spend some time looking around in the UI to familiarize yourself. It is a pretty nice way to see what is going on in your cluster. I personally really like the ability to go into a pod and being able to click on the “View logs” link in the top right corner, and see the logs there instead of having to use kubectl. Not to mention being able to “exec” into it for debugging!

Accessing the Dashboard 2.0

Ok, so using kubectl proxy works. We can access the dashboard. But it isn’t great. It has some pretty obvious limitations, like having only working on one some machines an only while the command is running. Not to mention a very sucky url to remember…

One solution would be to use kubectl port-forward instead, like this

kubectl port-forward service/kubernetes-dashboard -n kubernetes-dashboard 443:443

And then browse to https://localhost. But that still has some pretty serious limitations. It solves the hideous URL, but it still has the limitation of having to use kubectl to get it to work. But I think we should be able to use our newly learned knowledge about ingress controllers to make it better.

To start off, we need a new Ingress resource that looks like this

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: dashboard-ingress

namespace: kubernetes-dashboard

annotations:

nginx.ingress.kubernetes.io/backend-protocol: "HTTPS"

nginx.ingress.kubernetes.io/secure-backends: "true"

spec:

rules:

- host: dashboard.k8s.internal

http:

paths:

- path: /

backend:

serviceName: kubernetes-dashboard

servicePort: 443

It’s a little bit more complicated than the previous one you saw. The biggest change is that it is using HTTPS, so it requires us to add a couple of annotations to tell nginx to support HTTPS. Other than that, it is just a single rule that routes / to the kubernetes-dashboard service.

However, I did create a custom host for this scenario called dashboard.k8s.internal. To support that, I added 127.0.0.1 dashboard.k8s.internal to my hosts file to let Windows know that that host should route to 127.0.0.1.

Also, as you can see, this ingress is added to the kubernetes-dashboard namespace. This is because it routes to a service in that namespace.

kubectl apply -f ./dashboard-ingress.yaml

With the ingress in place, and the new entry in the hosts file, you should be able to reach the dashboard by browsing to https://dashboard.k8s.internal.

Note: Yes, the browser will puke TLS warnings all over the screen. That’s because the connection secured using a cert signed by a CA we don’t trust, so you have to tell the browser to ignore that. Setting up a trusted SSL cert is a little bit outside of the scope for this post…and to be honest, the encryption is still up and running…

That was pretty much the last real piece of information that I wanted to cover in this intro. The only thing I have left to show you are some kubectl commands that can be very useful to know.

kubectl tips

To me, I think you get away with knowing quite a small amount of kubectl commands to be honest. So I thought I would just mention the ones I think you absolutely need to know.

apply -f and create -f are two pretty obvious ones that you need to know of course. I generally only use apply though, as I don’t care if it is a create or an update. But if you really want to make sure it is a create, and not an update, then make sure you use create. Or, if you want to imperatively create a resource…

get is the way you get information about a specific resource. However, get in its default way of working doesn’t not actually get you all the information. If you want the full information about a resource, make sure you add an output using the --output or -o parameter. For example -o yaml. This will give you a lot more information about the resource, in your chosen format. There are several outputs formats you can use, including json and templates.

describe is another way to get information about a resource. It is very similar to __get -o

edit is a nice little helper method that allows you to view, edit and update a resource definition one go. Running it on my Windows machine pops up the spec in Notepad, allowing me to edit it. And as soon as I save the file and close Notepad, it updates the resource for me. I wouldn’t recommend using it in a production scenario as you generally want to make sure all your changes are source controlled so you know that has happened…but if you need something done fast, it is pretty useful.

explain is an AWESOME command. It gives you information about the resources type you want to create. It can give you details about every single setting you can use. You just give the the resource type as a parameter, for example kubectl describe pod, and it gives you information about all the top level fields you can configure on that type. And if you want to go deeper, you can give it a deeper path, for example running kubectl explain pod.spec gets all the information about the spec field, and what how you can configure it. Very useful!

Another thing that can be really useful is to “exec” into a temporary pod inside the cluster to do some debugging inside the cluster. You can do this by running something like this

kubectl run --generator=run-pod/v1 -it --rm temp --image=debian

This will create a temporary, interactive debian pod in the cluster that allows you to look around inside the cluster. And as soon as you disconnect, it is removed.

It is sometimes also useful to be able to attach to a running container as well. This can be done using kubectl exec -it like this

kubectl exec -it my-pod bash

This command will run bash interactively inside the pod my-pod. Or, if you just want to run a command inside the pod without being interactively attached, you can just run the same thing without -it, for example kubectl exec my-pod ls to list the directories in the current working directory of the pod my-pod.

Tip: There are a lot of really good help to find at https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/kubectl/cheatsheet/ as well!

Contexts

Finally, it is a good idea to know a little about kubectl contexts. kubectl is always working in a context. A context is a defined configuration that kubectl uses to figure out how to connect and authenticate with the cluster you want to work with. You can see the defined contexts on your machine by running

kubectl config get-contexts

Note: The one marked with * in the “CURRENT” column, the currently selected one…

If you want to change the context to use, you can run

kubectl config use-context <NAME OF CONTEXT>

A context is a combination of cluster connection info, a set of credentials and potentially a namespace. They are all stored in a config file on disk. And if you want to see the entire config, you can just run kubectl config view.

Generally, you don’t need to tweak this too much. But if you do, it is good to know that it is there. And that you can do it if necessary… To configure a new context, you need to define the involved parts to use. If you want to connect to a new cluster, you need to set one up like this

kubectl config set-cluster <CLUSTER NAME> --server=<CLUSTER ADDRESS>

Once you have a cluster, you need a set of credentials. This is dependent on how you authenticate. A very common way to do the authentication is to use client certificates. In that case, creating a set of credentials would look something like this

kubectl config set-credentials <CREDENTIAL NAME> --client-certificate=<CERT FILE> --client-key=<CERT KEY FILE>

Finally, you need to combine this information into a context by running

kubectl config set-context <CONTEXT NAME> --cluster=<CLUSTER NAME> --user=<CREDENTIAL NAME> [--namespace=<OPTIONAL NAMESPACE>]

This creates a new context that you can then use by executing kubectl config use-context <CONTEXT NAME>. This is very useful when you are working with multiple clusters. Something that generally happens much faster than you think. Pretty much at the same time as you set up a new cluster to be honest. At least if you also have Docker Desktop installed…

Note: If you are running Azure AKS, the Azure CLI can set up your context for you automatically. All you need to do, is to sign in with the CLI and then run az aks get-credentials -n <CLUSTER NAME> -g <RESOURCE GROUP>. This creates a new context, and sets it as the current straight away. Very nice and simple!

I think that was it! It ended up being a much longer intro series than I expected, and it took WAAAYYY too long to write. I am sorry about that! But now it is done at least. If you happened to stumble upon it after this post came on-line and didn’t have to wait for me to get the posts written, good for you! For the rest of you, once again, I am truly sorry!

Please feel free to reach out to me if you have any questions or thoughts, or if you are missing something! I’m available at @ZeroKoll!