Infrastructure as Code - An intro - Part 4 - Using Bicep

In the last post, I talked about IaC using ARM templates. In this post, I’m looking at ARM templates’ “sibling” Bicep.

There are a lot of complaints about ARM templates being too verbose and cumbersome to work with. Microsoft’s response to this is Bicep.

What is Bicep?

One of the interesting things about Bicep, is that it is basically just a nicer DSL (Domain Specific Language) on top of the ARM template language. This allows for a nicer syntax, while still being able to use the Azure Resource Manager to perform the work. Bicep files actually transpile into ARM templates before being sent to the Resource Manager. This way, the Resource Manager can be leveraged without having to be re-written to support the syntax.

Fun fact: As far as I understand, the name Bicep comes from it being a muscle in the arm… Get it? Bicep is a part of the ARM…

The fact that Bicep is just a nicer version of ARM templates, means that I don’t really need to walk you through how it works. All that was covered (somewhat briefly) in the previous post. So if you haven’t read that, and you are interested in how it works, I suggest doing so now.

And since it is really just a nicer syntax on top of ARM templates (at the moment), and the tooling is basically the same, a lot of this post will be spent comparing the two.

But enough of explanation about what the post will be about, let’s have a look at working with Bicep!

So…what do we need to install to work with Bicep files?

Bicep pre-requisites

Actually, the tooling is, as mentioned before, pretty much the same as for ARM templates. That means that you need the following

- Either Azure PowerShell or Azure CLI. (I’ll use Azure CLI in this post, as I find it much more logical)

- The Bicep CLI (more on this in a second)

- Some form of text editor. I suggest VS Code as it can provide some pretty awesome help when working with Bicep templates

- Optional: The VS Code Bicep extension. This will give you superpowers when working with Bicep in VS Code

Note: I’m going to assume that you have the Azure CLI installed. If you haven’t, I suggest going back to the post about the Azure CLI and having a look at how to install it.

Bicep CLI

To be able to work with Bicep files instead of ARM templates, you need the Bicep CLI. This is the part of the tool chain that is responsible for transpiling Bicep files to and from ARM templates. Yes…to AND from! More on that later!

The Bicep CLI is installed by running

> az bicep install

Or…if you are using Azure CLI version 2.20.0 or above, you can just ignore that step, as the Bicep CLI will be automatically installed when you run a command that needs it. So, in most cases, you don’t need to do anything to get Bicep file support on your machine.

Note: If you are on an earlier version of the Azure CLI, I would recommend updating that, instead of manually installing the Bicep CLI…

To verify your Azure CLI version, you can run

> az version

{

"azure-cli": "2.23.0",

...

}

And to verify the installed version of the Bicep CLI you can run

> az bicep version

Bicep CLI version 0.4.613 (d826ce8411)

If you try running this command without having the Bicep CLI installed, you get an error message that says

Bicep CLI not found. Install it now by running “az bicep install”.

And, as the error message says, you fix that by running az bicep install, or any Bicep related command that will automatically install it…

If you have an outdated Bicep CLI version, and want to update it to the latest and greatest, you just need to run

> az bicep upgrade

Once you have the Bicep CLI installed (or just want to ignore it and have the Azure CLI install it when needed), you need a text editor of some kind to edit the Bicep files.

VS Code and the Bicep extension

I would definitely suggest using VS Code when working with Bicep files. The reason for this, besides it being light-weight, cross platform, fast and generally quite awesome, is the ability to install the Bicep extension that gives you extra help when working with Bicep files.

The Bicep extension is available from the marketplace. Just search for bicep and you will find it.

That’s actually all there is to it from a tooling point of view. With these tools in place, we can start looking at setting up our infrastructure using Bicep.

Creating a Bicep file

“As usual”, I will be setting up the same infrastructure that I have been using in the previous posts. That means that I will set up

- A Resource Group to hold all of the resources

- An App Service Plan using the Free tier

- A Web App, inside the App Service Plan

- Application Insights (connected to the Web App)

- A Log Analytics Workspace to store the Application Insights telemetry

- A SQL Server Database

On top of that, I’ll connect the Web App to the SQL database by adding the connection string to the Connection Strings part of the Web App configuration, and to the Application Insights resource, by adding the required settings to the App Settings part of the configuration.

Ok…now that we have covered that (again), let’s create our first Bicep file, which I’ll call iac.bicep for this demo.

One of the nice things with Bicep, compared to ARM templates, is the fact that you don’t need to add any form of “base structure” to make it a valid Bicep file. ARM templates require us to create this JSON root element. In Bicep, as long as the file extension is .bicep, it is considered a Bicep file.

Now that we have a Bicep file in place, we can start defining our desired infrastructure inside it.

Adding the database

The first resource to be added is the database. It’s added by adding the following code

resource sqlServer 'Microsoft.Sql/servers@2021-02-01-preview' = {

name: 'mydemosqlserver123'

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

administratorLogin: 'server_admin'

administratorLoginPassword: 'P@ssw0rd1!'

}

}

As you probably noticed, the syntax is very similar to ARM templates. It’s just a lot less “JSON-y”.

Comment: Don’t miss the = sign before the { at the end of the first line. Personally, I think that could have been left out, as it’s a bit awkward and easy to miss, but I’m pretty sure that there is a reason for it being there…

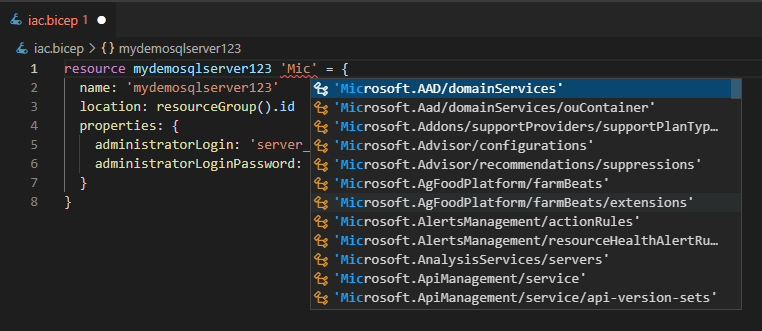

Using VS Code, with the Bicep extension installed, you will get nice little dropdowns with the available values, so you don’t have to remember it all by heart.

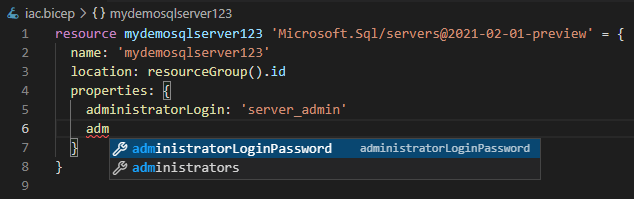

It even tells you what properties are available to be set for this resource type

And if you forget a mandatory value, it will make sure to tell you by adding a yellow squiggly line to your resource definition.

If you don’t remember the ARM template version of this, it looks like this

{

...

"resources": [

{

"name": "mydemosqlserver123",

"type": "Microsoft.Sql/servers",

"apiVersion": "2014-04-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"properties": {

"administratorLogin": "server_admin",

"administratorLoginPassword": "P@ssw0rd1!"

}

}

],

...

}

Let’s have a look at the differences between the two (besides the lack of JSON)…

First of all, when defining a resource in Bicep, you write resource <RESOURCE NAME> '<RESOURCE TYPE>@<API VERSION>', which is pretty much just a much denser version of what you use in the ARM template, where you need a type and apiVersion property to define the same stuff.

Also, Bicep’s lack of a “root element” makes it a lot nicer to read in my opinion. In “Bicep land” we don’t need the root element, since the file defines scope of the template. Anything placed inside the file is considered a part of the template.

Another thing to note is the fact that each resource in Bicep gets a “resource name”. This has nothing to do with the generated resource. Instead, it is used when referring to the resource from other parts of the template. This makes referencing resources a lot easier in Bicep, than using the long, string-based IDs that you are forced to use in ARM templates.

Other than that, there are some other minor syntax changes that are quite nice.

First of all, strings have to use single quotes ('<STRING>'). This is not a biggie as such. However, I find that with JSON allowing you to use both single and double quotes, I often end up using both versions in my templates, which annoys me when I read it later on. I guess that can be sorted by just choosing one. But I still like Bicep forcing me down a single path.

You also don’t need to wrap your expressions in brackets ([<EXPRESSION>]) in Bicep. Instead, you just add them without quotes, and you are good to go. For example, for the location property we use resourceGroup().location in Bicep, instead of "[resourceGroup().location]" like you would in ARM templates. Another minor difference, but it makes it a whole lot easier to read (and write).

The content of the resource definition is still pretty much the same though. You still have the same values to set, and can use the same functions when doing it. This makes the move from ARM templates to Bicep quite easy. And if you are going straight to Bicep without ever using ARM templates, you should still be able to convert any ARM template snippet you find on the internet to Bicep quite easily.

Note: As of version 0.3, Bicep is supported by Microsoft Support Plans, and has 100% feature parity with ARM.

Building (and decompiling) Bicep files

Now that we have a fully formed Bicep file, we can verify that it is syntactically correct by building it. Building a Bicep file transpiles it to an ARM template.

To build the iac.bicep file, we can execute the following command

> az bicep build --file iac.bicep

This will create an iac.json file that looks like this

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentTemplate.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"metadata": {

"_generator": {

"name": "bicep",

"version": "0.4.613.9944",

"templateHash": "11357509686250702948"

}

},

"functions": [],

"resources": [

{

"type": "Microsoft.Sql/servers",

"apiVersion": "2021-02-01-preview",

"name": "mydemosqlserver123",

"location": "[resourceGroup().id]",

"properties": {

"administratorLogin": "server_admin",

"administratorLoginPassword": "P@ssw0rd1!"

}

}

]

}

This clearly shows the difference in verbosity between Bicep and ARM templates. 8 vs 24 lines of code. For a single resource! That’s awesome!

Note: This difference do get less and less the more configuration you add. Using a very simple resource like this in a comparison isn’t really fair, as most of the change in verbosity comes from the resource declaration part, not the actual configuration. So the more configuration we add, the smaller the difference becomes.

Another cool Bicep trick is the ability to decompile an ARM-template into a Bicep file. We can try this with the ARM template that we just created, by running

> az bicep decompile --file iac.json

This will decompile the iac.json ARM template to an iac.bicep file that looks exactly like the file we just wrote manually.

Warning: It will actually overwrite the existing Bicep file, as the decompiled file will have the same name as the original Bicep file. But in this case that doesn’t matter, because the output is identical.

Comment: If you want to export a Resource Group from Azure to Bicep, it is unfortunately a two step procedure (at the moment). But at least it’s two easy steps. Just export it to an ARM template first, and then decompile that to Bicep.

The next step is to add the SQL database to the SQL Server. And once again, it looks very similar to the ARM version

...

resource db 'Microsoft.Sql/servers/databases@2014-04-01' = {

parent: sqlServer

name: 'MyDemoDb'

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

collation: 'SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS'

requestedServiceObjectiveName: 'Basic'

}

}

However, there are some really awesome things going on in here. Or at least one…the parent property. This defines that there is a parent/child relationship between the two resources. This not only shows the semantic relationship to the reader of the Bicep file, it is also used in such a way that we do not need to add a dependsOn property to the child resource. Instead, the Bicep transpiler understands this relationship, and automatically adds the dependsOn in the ARM template during build. Very nice!

Also, the parent is defined using only the name of the resource it depends on, sqlServer in this case, instead of the full ID ([resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', 'mydemosqlserver123')]) that you are forced to use in ARM templates.

There is also another syntax available to define a parent/child relationship, and that is to define the child resource inside its parent, just as you would in an ARM template. However, in the Bicep case, you don’t need to define an extra resources property. Instead, you just declare the resource inside the parent like this

resource sqlServer 'Microsoft.Sql/servers@2021-02-01-preview' = {

name: 'mydemosqlserver123'

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

administratorLogin: 'server_admin'

administratorLoginPassword: 'P@ssw0rd1!'

}

resource db 'databases@2014-04-01' = {

name: 'MyDemoDb'

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

collation: 'SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS'

requestedServiceObjectiveName: 'Basic'

}

}

}

As you might have noticed, with this way of defining the child resource, the type is simplified Microsoft.Sql/servers/databases down to databases. Just as you would in an ARM template. And the parent property can obviously be removed, as the relationship is defined by the resource being defined “inside” the parent.

Note: Personally I prefer this way of defining parent/child resources, as shows the relationship in a very explicit way. No need to try and locate a parent property, just look at the location of the declaration!

The last step in the SQL set up, is to add a firewall rule that allows access to the database from all Azure based resources. And once again, there is a parent/child relationship between this resource and the SQL Server, so I’ll add it inside the server resource like this

resource sqlServer 'Microsoft.Sql/servers@2021-02-01-preview' = {

...

resource fwRule 'firewallRules@2021-02-01-preview' = {

name: 'AllowAllWindowsAzureIps'

properties: {

startIpAddress: '0.0.0.0'

endIpAddress: '0.0.0.0'

}

}

}

That makes the resource definition quite simple, as it reduces the type from Microsoft.Sql/servers/firewallRules to firewallRules, and removes the need for a parent property.

Ok, that’s it! Now we have a Bicep file that sets up the required database for us. And we can verify that the syntax is correct, by build it using az bicep build.

Before we go any further, let’s just try and deploy the Bicep file to the cloud by running

> az group create -n MyDemoGroup -l WestEurope

> az deployment group create -f ./iac.bicep -g MyDemoGroup -n MyDemoDeployment

The first command creates an empty Resource Group to deploy the resources to. And the second uses the Bicep file to tell the Azure Resource Manager what infrastructure we want to have.

Note: Running the above commands will actually fail… The reason for this is that the SQL Server name needs to be unique, and apparently mydemosqlserver123 isn’t. So if you really want to try deploying it at this point, you will need to update the SQL Server resource with a more unique name, before running the command…

Before we go any further, I suggest removing any resources that were just created. Moving forward, we will change the resource names, causing a new set of resources to be created… And there is no reason to have multiple SQL Server instances costing money.

Luckily, with all the resources in a single Resource Group, this can easily be accomplished just deleting the whole Resource Group ike this

az group delete -n MyDemoGroup

Variables

In the previous post, I talked a bit about treating resources as cattle instead of pets. A practice that would have solved the SQL Server deployment issue.

If I had named the SQL Server using a “cattle naming standard”, the name conflict is unlikely to have happened. So let’s go ahead and introduce “cattle” based naming strategy in our Bicep file using variables.

In Bicep, variables are just defined as var. Nice and simple! So, to get a more cattle like naming convention, we can write something like this

var suffix = uniqueString(resourceGroup().id)

var sqlName = 'mydemosqlserver123${suffix}'

resource sqlServer 'Microsoft.Sql/servers@2021-02-01-preview' = {

name: sqlName

location: resourceGroup().location

...

}

As you can see, we define 2 variables, one called suffix, that uses the uniqueString() function to create a unique suffix, and one called sqlName, that combines the existing server name with the suffix, using the ${} interpolation syntax.

The server’s name property is then set to sqlName.

Note: You can obviously still use the concat() or format() functions to format and concatenate the string. However, I would recommend using the interpolation syntax, as it is easier to read and understand.

I personally find the variable syntax much better in Bicep than in ARM templates, where it just feels a bit awkward. However, the use of a variable for the SQL Server name like this becomes less interesting in Bicep than in an ARM template. The reason for this, is that we do not reference the SQL Server resource using the name, like we do in ARM templates. Instead, we reference it using the resource name. This means that the sqlName variable will really only be used in one place, instead of being used in every single resource reference. Because of this, it might actually be better to just define it in-line like this

resource sqlServer 'Microsoft.Sql/servers@2021-02-01-preview' = {

name: 'mydemosqlserver123${uniqueString(resourceGroup().id)}'

...

}

I still wanted to show the fact that you can use variables just as you would in ARM templates though, since there are many other scenarios where the use of variables can make life a lot easier.

Adding the Log Analytics Workspace

The next step is to create the Log Analytics Workspace that will be used by Application Insights to store its telemetry. This means adding a new resources to the Bicep file like this

resource law 'Microsoft.OperationalInsights/workspaces@2021-06-01' = {

name: 'MyDemoWorkspace${uniqueString(resourceGroup().id)}'

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

sku: {

name: 'Free'

}

}

}

When I came to this point in the post about ARM templates, I decided to keep my code a bit more “DRY” by abstracting the naming convention into a user-defined function. Unfortunately, Bicep doesn’t support user-defined functions at this time.

As far as I understand, they are looking at adding it to the Bicep language, but it seems like there are some improvements that they want to add to the ARM templates before adding support for it in Bicep. So, I guess we will have to make do without user-defined functions at this point, and just accept a bit more repetition in this case.

However, if you want use the same naming standard that was used in the ARM template post, and I suggest you do, you just need to add a couple of variables and update the names in the Bicep file like this

var projectName = 'MyDemo'

var suffix = uniqueString(resourceGroup().id)

resource sqlServer 'Microsoft.Sql/servers@2021-02-01-preview' = {

name: toLower('${projectName}-sql-${suffix}')

...

}

...

resource law 'Microsoft.OperationalInsights/workspaces@2021-06-01' = {

name: '${projectName}-ws-${suffix}'

...

}

This will make sure your resources are named using a nice naming standard, while will making it easy to change the project name and suffix if needed. Unfortunately, it isn’t quite as flexible as a user-defined function, but it works.

Creating the Web App

With the resources required by the Web App in place, we can shift our focus to setting up that part. That means that we need to add an App Service Plan, and a Web App like this

...

resource appSvcPlan 'Microsoft.Web/serverfarms@2021-01-15' = {

name: '${projectName}-plan-${suffix}'

location: resourceGroup().location

sku: {

name: 'F1'

capacity: 1

}

}

resource web 'Microsoft.Web/sites@2021-01-15' = {

name: '${projectName}-app-${suffix}'

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

serverFarmId: appSvcPlan.id

siteConfig: {

netFrameworkVersion: 'v5.0'

connectionStrings: [

{

name: 'connectionstring'

connectionString: 'Data Source=tcp:${reference(sqlServer.id).fullyQualifiedDomainName},1433;Initial Catalog=${sqlServer::db.name};User Id=server_admin;Password=\'P@ssw0rd1!\';'

type: 'SQLAzure'

}

]

}

}

dependsOn: [

sqlServer

]

}

It is once again a fairly straight forward addition of 2 resources, a “server farm” a.k.a App Service Plan, and a Web App. However, the Web App configuration is a bit more extensive than the rest of resources, as it needs a .NET Framework version and a SQL connection string to be added.

Note: Yes, I am hard coding the credentials to the database, which is a REALLY bad idea… It will be fixed soon, I promise! Do NOT put credentials in your code!

One interesting thing to look at here is the reference to the database name. The syntax for this is sqlServer::db.name. The reason for this is that the database (db) is a child resource of sqlServer. This require us to use this syntax where you prefix the resource name with the parent name and then ::. Not too complicated, but definitely worth pointing out. Luckily, the VS Code Bicep extension will tell you if you mess up…

Also, instead of having to concatenate strings to be abe to pass the ID of the SQL Server to the reference() function, we can just use sqlServer.id. Nice!

The last piece of the puzzle is the addition of Application Insights.

Adding Application Insights

The problem with this resource is that the Web App needs some of the information from that resource to work, but the Application Insights resource also needs information about the Web App it is connected to. So it’s a bit of a catch 22. But let’s go ahead and sort that out!

The first part is to add the Application Insights resource like this

resource ai 'Microsoft.Insights/components@2020-02-02' = {

name: '${projectName}-ai-${suffix}'

location: resourceGroup().location

kind: 'web'

tags: {

'hidden-link:${web.id}': 'Resource'

}

properties: {

Application_Type: 'web'

WorkspaceResourceId: law.id

}

dependsOn: [

web

]

}

This creates an Application Insights resource, connected to the Log Analytics Workspace that we defined earlier, using the WorkspaceResourceId property. It also adds a hidden-link tag that is used internally by Azure to see the relationship between the Application Insights resource, and the Web App.

The hidden-link tag is a bit awkward as the name of the tag needs to include the ID of the Web App. For this reason, we have to use a bit of string interpolation to get the tag name to include the required ID.

Other than that, it is pretty straight forward I think…

The last step is to configure the Web App’s app settings to include the required Application Insights keys. However, since we have already defined the Web App resource, and we have that circular reference situation with the Application Insights resource, we need to add this part of the Web App configuration separately. Luckily, we can defines this in a separate config resource that looks like this

resource webAppSettings 'Microsoft.Web/sites/config@2021-01-15' = {

name: '${web.name}/web'

properties: {

appSettings: [

{

name: 'APPINSIGHTS_INSTRUMENTATIONKEY'

value: reference(ai.id).InstrumentationKey

}

{

name: 'ApplicationInsightsAgent_EXTENSION_VERSION'

value: '~2'

}

{

name: 'XDT_MicrosoftApplicationInsights_Mode'

value: 'recommended'

}

]

}

dependsOn: [

web

ai

]

}

Since this is technically a child resource to the Web App, as the type Microsoft.Web/sites/config is “below” Microsoft.Web/sites, the name has to be a combination of the parent name and “something”. In this case, it needs to be a combination of the parent name and web. Because of this, the name is defined using string interpolation, '${web.name}/web'. Other than that, it is pretty much just another resource, that in the end will add 3 settings to the Web App’s appSettings property.

That pretty much concludes the Bicep file. However, there are a couple of hard coded values that I dislike. So, just as when I created the ARM template in the previous post, I want to add a couple of input parameters that we can use to configure the infrastructure during deployment.

Adding Parameters

In Bicep, an input parameter is declared much like variables, but using the keyword param and defining a type. Like this

param projectName string

We can also give it a default value that is used if it isn’t defined during deployment. That looks like this

param sqlSize string = 'S0'

However, it’s also possible to add other metadata to parameters using an attribute syntax that looks like this

@allowed([

'Basic'

'S0'

'S1'

'S2'

'P1'

'P2'

])

@description('The SQL Server database size')

param sqlSize string = 'S0'

Together, these attributes add a descriptive text that explains what the parameter is used for, as well as limits the allowed values to a defined set of options. However, there are quite a few more attributes available for you to use, if you for example want to limit input lengths or make sure the parameter value is treated as a sensitive value.

In this case, I’m want to add a few parameters that will both allow us to configure the created resources, but also get away from the hard-coded credentials. So I’ve decided to add the following parameters

@description('The name of the application')

param projectName string

@allowed([

'Basic'

'S0'

'S1'

'S2'

'P1'

'P2'

])

@description('The SQL Server database size')

param sqlSize string = 'S0'

@description('The username to use for the SQL Server Admin')

param sqlUser string = 'server_admin'

@secure()

@description('The password to use for the SQL Server Admin')

param sqlPwd string

@allowed([

'F1'

'B1'

'B2'

'S1'

'S2'

'P1'

'P2'

])

@description('The service plan size')

param appSvcPlanSku string = 'F1'

These parameters names should be pretty self explanatory, but I have still added a @description() attribute to them to make sure. And for the ones where it makes sense, I have also added @allowed() and/or default values.

For the sqlPwd I have also made sure to add the @secure() attribute to make sure it is handled in a secure way. That is, it isn’t added to any log output etc.

Note: The projectName variable has also been replaced by a parameter

With these new parameters in place, the Bicep file looks as follows

@description('The name of the application')

param projectName string

@allowed([

'Basic'

'S0'

'S1'

'S2'

'P1'

'P2'

])

@description('The SQL Server database size')

param sqlSize string = 'S0'

@description('The username to use for the SQL Server Admin')

param sqlUser string = 'server_admin'

@secure()

@description('The password to use for the SQL Server Admin')

param sqlPwd string

@allowed([

'F1'

'B1'

'B2'

'S1'

'S2'

'P1'

'P2'

])

@description('The service plan size')

param appSvcPlanSku string = 'F1'

var suffix = uniqueString(resourceGroup().id)

resource sqlServer 'Microsoft.Sql/servers@2021-02-01-preview' = {

name: toLower('${projectName}-sql-${suffix}')

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

administratorLogin: sqlUser

administratorLoginPassword: sqlPwd

}

resource db 'databases@2014-04-01' = {

name: 'MyDemoDb'

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

collation: 'SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS'

requestedServiceObjectiveName: sqlSize

}

}

resource fwRule 'firewallRules@2021-02-01-preview' = {

name: 'AllowAllWindowsAzureIps'

properties: {

startIpAddress: '0.0.0.0'

endIpAddress: '0.0.0.0'

}

}

}

resource law 'Microsoft.OperationalInsights/workspaces@2021-06-01' = {

name: '${projectName}-ws-${suffix}'

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

sku: {

name: 'Free'

}

}

}

resource appSvcPlan 'Microsoft.Web/serverfarms@2021-01-15' = {

name: '${projectName}-plan-${suffix}'

location: resourceGroup().location

sku: {

name: appSvcPlanSku

capacity: 1

}

}

resource web 'Microsoft.Web/sites@2021-01-15' = {

name: '${projectName}-app-${suffix}'

location: resourceGroup().location

properties: {

serverFarmId: appSvcPlan.id

siteConfig: {

netFrameworkVersion: 'v5.0'

connectionStrings: [

{

name: 'connectionstring'

connectionString: 'Data Source=tcp:${reference(sqlServer.id).fullyQualifiedDomainName},1433;Initial Catalog=${sqlServer::db.name};User Id=${sqlUser};Password=\'${sqlPwd}\';'

type: 'SQLAzure'

}

]

}

}

dependsOn: [

sqlServer

]

}

resource ai 'Microsoft.Insights/components@2020-02-02' = {

name: '${projectName}-ai-${suffix}'

location: resourceGroup().location

kind: 'web'

tags: {

'hidden-link:${web.id}': 'Resource'

}

properties: {

Application_Type: 'web'

WorkspaceResourceId: law.id

}

dependsOn: [

web

]

}

resource webAppSettings 'Microsoft.Web/sites/config@2021-01-15' = {

name: '${web.name}/web'

properties: {

appSettings: [

{

name: 'APPINSIGHTS_INSTRUMENTATIONKEY'

value: reference(ai.id).InstrumentationKey

}

{

name: 'ApplicationInsightsAgent_EXTENSION_VERSION'

value: '~2'

}

{

name: 'XDT_MicrosoftApplicationInsights_Mode'

value: 'recommended'

}

]

}

dependsOn: [

web

ai

]

}

That’s a lot of code, I know! But that the whole template for setting up a Web App with a database and Application Insights monitoring.

However, now that we have added parameters, the deployment of the template changes a bit, as we have to define the parameters values we want to use. At least the ones that don’t have a default value…

If you just run az deployment group create -f ./iac.bicep -g MyDemoGroup -n MyDemoDeployment like before, you will be asked to provide values for the parameters that are missing defaults. However, in a non-interactive environment, like a deployment pipeline, this kind of sucks. So, you generally provide the values to the deployment either by passing them to the command using the --parameters parameter, or by passing the path to a file that contains the values to the --parameters parameter.

Note: Yes, you use the same parameter for “manual” parameters and a file path, which is a bit weird I think. You can also define a combination “manual” values and a file by using multiple --parameters inputs.

If you want to use “manual” parameters, it would look something like this

> az deployment group create -f ./iac.bicep -g MyDemoGroup --parameters projectName=MyDemo sqlPwd='P@ssword1!'

As you can see, you send as many values as you want to the --parameters parameter, using a space separated string.

And if you want to use a parameters file, you need to first create a parameters file that looks something like this

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentParameters.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"parameters": {

"projectName": { "value": "MyDemo" },

"sqlPwd": { "value": "P@ssword1!" }

}

}

Yes, that is JSON…and yes, that is the same format that is used by ARM templates… So if you have used ARM templates before, it should look pretty familiar.

This file can then be passed to the --parameters parameter like this

> az deployment group create -f ./iac.bicep -g MyDemoGroup --parameters ./my-parameters.json

And finally, if you wanted to combine the two, it would look like this

> az deployment group create -f ./iac.bicep -g MyDemoGroup --parameters ./my-parameters.json --parameters sqlPwd='P@ssword1!'

Cool! Now we have a complete template, and the ability to configure it using input parameters. However, there is still one more thing we can do.

Outputs

When you create your infrastructure using code, you often generate information etc that you need in other parts of the system. For example, you might need the address to the Web App, or the connection string to the database. And because they are needed outside the IaC code, they need to be made available to the outside somehow. In Bicep/ARM templates the solution to this is to use “outputs”.

Outputs are basically just values that you want to make available to the outside after a deployment has been made.

In Bicep, outputs are defined a lot like variables and parameters. However, instead of the param or var keyword, they use the output keyword. And obviously, they need to have a value set…

In the current deployment, where we are using an automated naming strategy, it could be useful to get hold of the URL of the deployed Web App at the end. So to add that information as an output, we can add the following to the Bicep file

output websiteAddress string = 'https://${reference(web).defaultHostName}/'

This will give us an output called websiteAddress that will contain the URL to the website. However, since the Web App only gives us the defaultHostName to work with, we can use some string interpolation to add “https://” at the beginning, and “/” at the end, to get a fully formed URL.

With that output in place, if we create a new deployment, that information is now available to us using the Azure CLI. All you need toi do is to run

> az deployment group show `

-g MyDemoGroup `

-n MyDemo

{

"id": "/subscriptions/ba40d97f-a1a4-4a24-9f9b-f0d70b447d1f/resourceGroups/MyDemoGroup/providers/Microsoft.Resources/deployments/MyDemo",

"location": null,

"name": "MyDemo",

...

}

This gives us all the information available about the deployment in question. Unfortunately, that contains a lot of information, including the output that we are interested in. And even if we could parse the returned JSON, and get the value from that, there is an easier way. We just need to use the --query and -o parameters of the Azure CLI like this

> az deployment group show `

-g MyDemoGroup `

-n MyDemo `

--query properties.outputs.websiteAddress.value `

-o tsv

https://mydemo-app-ssar56zos4p6k.azurewebsites.net/

That’s pretty useful!

Note: Don’t forget to clean up the resources once you are done playing with the template! (az group delete -n MyDemoGroup -y)

Conclusion

Well, the pros and cons of Bicep and ARM templates are pretty much the same for obvious reasons. However, I find Bicep nicer to work with, even if does get more verbose than this simple sample. It’s definitely powerful and can do most of the things we need to get an infrastructure up and running. It would also be my bet for the future. Sure, ARM templates need to support pretty much any feature that Bicep uses, in some way. But I think the main focus from Microsoft, when it comes to the end-user experience, will go into Bicep.

So, now you have seen both versions of Microsoft’s offering. In the next post, I’m moving away from the Microsoft specific and have a look at Terraform.

If you have any questions or comments, feel free to reach out at @ZeroKoll as usual!

Extra tip: If you want to play around a bit more with Bicep, I suggest having a look at the Bicep learning path at Microsoft Docs. This will give you a deeper introduction to Bicep in an easy to digest format.