Infrastructure as Code - An intro - Part 3 - Using ARM

In this 3rd post in my series about IaC, it is time to move away from the imperative approach, and start looking at doing it declaratively. And for that, I have decided to start off by looking at Azure ARM templates.

I know that some people are questioning why I would even cover ARM templates, when there are so many other, “better” options out there. Not to mention that ARM templates are likely to be replaced in the general public by Bicep, which we will look at in a later post. The answer to this is that I find ARM templates such an integral part of Azure IaC that I think leaving it out would be a mistake. So here we go, let’s have a look at ARM templates.

What is ARM and ARM templates?

ARM stands for Azure Resource Manager, which the part of Azure that manages your resources (doh…it is in the name…). At least now. It used to be managed in a different way, which can still be seen today in the Azure Portal, where it is referred to as “classic deployment”. But let’s not get to bogged down about the way it used to be, and instead look at current situation.

The Azure Resource Manager is told what to create using templates. These templates are written in JSON, and uploaded to the resource manager. The resource manager then figures out what needs to be created, deleted or updated to make the world match the template.

“Unfortunately”, ARM templates are written in this verbose, cumbersome JSON, which is probably the biggest pet peeve that people have with this technology. And I agree to be honest. It feels unnecessarily complex and cumbersome to work with, when it could have been made a lot easier I think.

On the other hand, even if they are a handful to work with, they are still the foundation on top of which a lot of the other tools build. For example, the new and shiny Bicep, is basically just a nicer, cleaner way to create ARM templates. So, in the end, it is still ARM under the hood. So understanding ARM can definitely make a lot of things easier. Especially when you start getting into debugging…

Since creating creating templates from scratch is a bit of a PITA, a lot of people even suggest that you create your initial templates by first creating the desired infrastructure in the Azure Portal, and then export the templates for that infrastructure. These templates can then be modified to fit what you need. And even if I don’t think creating the templates from scratch is a massive PITS, this can definitely be the fastest way to get an ARM templates that works for you. Depending on how complex an infrastructure you are creating.

Exporting ARM templates

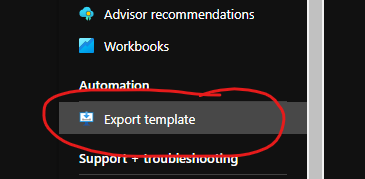

To use the Azure Portal to create the base for your ARM templates, you need to first set up your infrastructure using the Portal, PowerShell or Azure CLI. Once you have the desired infrastructure, you can go to the Resource Group you want to turn into an ARM template and look for this menu option

Pressing that will show you the generated template, as well as allow you to download the template. And by template, I mean a ZIP file with two (or more depending on the infrastructure size) JSON files. One called template.json, and one called parameters.json.

Once you have the template files, you can open then in whatever JSON editor you like and modify them to your hearts content.

I won’t cover the contents of an exported template in this post. Instead, I will show you how we can build a template from scratch. But I do want to highlight that the templates you get from the portal have a lot of the configuration for your resources hard coded, based on the current infrastructure configuration. The only thing that is really turned into parameters are the names of the resources.

On top of values being hard coded, the template also tends to contain quite a few extra parameters that you generally don’t need to set. Not to mention a bunch of resources that you haven’t specifically created, but are created by Azure behind the scenes for you. Making the template a lot more complicated than it needs to be. The reason for this is that the generated template is a snapshot of all the included resources. So if you want to use these as the starting point for your template, I suggest cleaning it up quite a bit, to make it smaller and easier to read. I also suggest converting some of the settings to parameters, making the template more flexible.

Note: Just for “fun”, I exported the template for the infrastructure that was set up in the previous post, using approximately 20 lines of Azure CLI commands. It ended up with an ARM template that was 1638(!) lines of JSON… Let’s see how lines it ends up being when we set up the same infrastructure using a handcrafted ARM template!

As I mentioned before, I find this template export strategy to be a quick way to get a template up and going. However, due to the massive amount of “stuff” in it, as well as a few other reasons, I still think creating templates from scratch is the way to go. So I’m going to show you how to do that now. This will not only give you a smaller template, it will also give you a much better understanding of what is happening in the template.

ARM pre-requisites

Before we can start creating our own ARM templates, there are a couple of things you need installed on your machine.

First of all, you need some form of JSON editor. I suggest using VS Code as it is free, and pretty great for this specific task. If you haven’t got it installed, you can use any test/JSON editor you want, including Notepad. Or, you can go and download it at https://code.visualstudio.com/download.

If you are using VS Code, I also suggest installing the Azure Resource Manager (ARM) Tools extension. It has snippets and other helpful features that will help you while you are crafting your ARM templates.

Once you have your template, you also need a way to deploy it. For this, you need either Azure PowerShell or the Azure CLI. As you might have seen in my previous post I am not a huge fan of Azure PowerShell, so I suggest installing the Azure CLI instead.

With the Azure CLI (or Azure PowerShell) installed, you need to authenticate yourself, and potentially choose the correct subscription. This was covered in my previous post about Azure CLI. So if you are wondering how to do that, I suggest going back and reviewing that part of that post.

Note: If you already have the Azure CLI installed, make sure that you are using version 2.6 or later. You can verify this by running az --version and looking at the azure-cli version.

Creating an ARM template

In this post, I’m going to create the same infrastructure that was created in the previous post (and will be created in all future posts in this series). That is

- A Resource Group to hold all of the resources

- An App Service Plan using the Free tier

- A Web App, inside the App Service Plan

- Application Insights (connected to the Web App)

- A Log Analytics Workspace to store the Application Insights telemetry

- A SQL Server Database

Obviously the connection string to the SQL database needs to be set up in the Connection Strings part of the Web App configuration. The Web App will also need to have the required the Application Insights settings added to the App Settings part of the configuration for it to work.

So, now that you know what we are building, we can get started.

The first thing that we need is an ARM-template file. So let’s go ahead and create a file called iac.json, and add the JSON needed to make it an ARM template. It looks like this

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentTemplate.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"parameters": {},

"functions": [],

"variables": {},

"resources": [],

"outputs": {}

}

As you can see, it is a standard JSON object definition, with $schema and contentVersion properties added to it. These properties make it an ARM template. On top of those, there are 5 different “sections”. Each containing its own subset of ARM template resources.

Note: I generated the above JSON in VS Code using the arm! snippet from the Azure Resource Manager (ARM) Tools.

Now that we have the skeleton for our template, let’s start adding stuff to it!

Adding the database

In the last post, the first resource we created was a Resource Group. However, when working with ARM templates, the resource manager assumes that there already is a Resource Group to work with. And on top of that, it assumes that you want to deploy all of your resources into that one Resource Group. If you need to deploy resources to multiple Resource Groups, you need to use something called nested templates.

Comment: In our case, it is fine to use a single Resource Group, and define all resources in a single template. However, I thought I would mention the ability to use nested templates as well, as you might need them in the future.

Since we don’t need to define the Resource Group, we can move straight to defining the SQL Server and SQL Database.

Any resource that needs to be defined, is added by adding a JSON object in the resources array. So to add a SQL Server resource to the template we add the following

{

...

"resources": [

{

"name": "mydemosqlserver123",

"type": "Microsoft.Sql/servers",

"apiVersion": "2014-04-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"properties": {

"administratorLogin": "server_admin",

"administratorLoginPassword": "P@ssw0rd1!"

}

}

],

...

}

Each resource has to have a name, a type and apiVersion. Most of them also have a location and properties property.

I think all of the parameters are pretty self explanatory. However, one thing to note is the value set for the location property. The [...] syntax means that it is an evaluated expression. That is, a bit of code that will be evaluated before the JSON is used. In this case, it references the current Resource Group using the resourceGroup() function, and then uses the location property from that, to set value for the SQL Server’s location property. Making sure that the SQL Server is created in the same geographical location as the Resource Group.

It might also be worth noting that some resources have limitations on the name value. SQL Server for example, requires it to be lower-case letters a-z, numbers 0-9 and hyphen only. If you try using something else, you will be told so by when trying to deploy your template.

Once the SQL Server instance is up and running, we need to set up the database inside it. This is done by adding another resource that looks like this

{

...

"resources": [

...

{

"name": "mydemosqlserver123/MyDemoDb",

"type": "Microsoft.Sql/servers/databases",

"apiVersion": "2014-04-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"properties": {

"collation": "SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS",

"edition": "Basic",

"maxSizeBytes": "1073741824",

"requestedServiceObjectiveName": "Basic"

},

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', 'mydemosqlserver123')]"

]

}

],

...

}

Ok, this has a bit more stuff going on than the server. However, most of the setup is pretty easy to understand I think. The hard part when it comes to ARM templates is really to figure what configuration is available. Luckily, this is pretty well documented at https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/templates/.

However, there are 2 things that are important to note in the resource definition above. First of all, the name parameter has to be a combination of the SQL Server name and the SQL Database name, with a slash in between. That’s just the way it works… And secondly, there is a dependsOn array for this resource. This array defines what other resources this resource depends on. And thus, what other resources need to be created before the current one. In this case, it tells the resource manager that the SQL Server needs to be created before the database can be created.

To define a “dependsOn relationship”, you need to define the full ID of the resource that it depends on. This can be done by using the resourceId() function. This function helps you to get hold of a resource ID by passing in the resource type and the name of the resource.

Note: The resourceId() function can be used to reference resource in other subscriptions etc as well. But it’s mostly used by passing in the type and name.

As for the properties, they are just the basics for setting up a SQL Database.

However, there is also another way to define the database. As the database is logically placed “underneath” the server, it can be added as a sub-resource to the SQL Server resource.

Note: By “logically placed underneath” I mean that the type definition is “underneath” the server’s. In this case Microsoft.Sql/servers/databases, which is “under” Microsoft.Sql/servers. Any resource that has a type that is “below” another type can be added as a sub-resource.

Doing it this way would look like this

{

...

"resources": [

{

"name": "mydemosqlserver123",

"type": "Microsoft.Sql/servers",

"apiVersion": "2014-04-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"properties": {

"administratorLogin": "server_admin",

"administratorLoginPassword": "P@ssw0rd1!"

},

"resources": [

{

"name": "MyDemoDb",

"type": "databases",

"apiVersion": "2014-04-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', 'mydemosqlserver123')]"

],

"properties": {

"collation": "SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS",

"requestedServiceObjectiveName": "Basic"

}

}

]

}

],

...

}

This has a couple of benefits. First of all, it indicates a relationship between the two resources. However, you still need to add a dependsOn. Having it as a sub-resource only declares the semantic relationship, not really the physical dependence.

On top of that, it allows us to simplify the type and name values as they are automatically prefixed with the parent info. So instead of Microsoft.Sql/servers/databases and mydemosqlserver123/MyDemoDb, we can simplify it down to the much simpler databases and MyDemoDb.

The last part of the SQL set up is to add a firewall rule that allows Azure services to access the database. This can once again be done by adding either a new “root” resource, or a sub resource, as it is logically placed “underneath” the server. I’ll choose the sub-resource path as I prefer reading that

{

...

"resources": [

...

{

"type": "firewallRules",

"apiVersion": "2021-02-01-preview",

"name": "AllowAllWindowsAzureIps",

"properties": {

"startIpAddress": "0.0.0.0",

"endIpAddress": "0.0.0.0"

},

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', 'mydemosqlserver123')]"

]

}

]

}

That’s it! That should add a firewall rule that allows any traffic that originates from Azure service through.

Note: Yes, it is really odd to set startIpAddress and endIpAddress to 0.0.0.0. But that’s just the way you define “all Azure services”.

Let’s go ahead and verify that the stuff we have written so far actually works, by trying to deploy it to Azure. This is done by running

az deployment group create -g MyDemoGroup -n MyDemo --template-file iac.json

This command defines what Resource Group (-g) to deploy it to, as well as a name (-n) for the current deployment. The name is than used for future deployments to figure out what resources have changed.

This command takes a while to run, but it should work as expected. If it doesn’t, if for example you used a SQL Server name that was already taken, you will get an error (JSON-formatted) explaining what caused the problem.

Warning: Make sure that the selected Resource Group, in this case MyDemoGroup, is already created. Otherwise you will end up with an error that looks like this {“error”:{“code”:”ResourceGroupNotFound”,”message”:”Resource group ‘MyDemoGroup’ could not be found.”}}

Before we go any further, I suggest removing the resources that were just created. The reason for this is that we are about to make some changes to the resource names, causing new resources to be created… Luckily, with the resources in a single Resource Group, that can easily be accomplished by running

az group delete -n MyDemoGroup

Depending on the name of the Resource Group you were using…

Variables

Before we go any further, I want to clean up the current template a bit… So far we have added 3 resources, and already we have quite a lot of duplication when it comes to the SQL Server name for example. It is not only used for the name parameter for the server, but also for “all” the dependsOn values. If we decided to change that name, that could cause some issues. And even if a “find & replace” could probably sort it in this case, a bit of refactoring seems like a better idea.

In this case, we can solve the duplication using variables. These are basically named values declared in the variables section, that can be referenced throughout the template.

So, to sort out our current duplication of the SQL Server name, let’s convert it to a variable.

First we add the variable

{

...

"variables": {

"sqlServerName": "mydemosqlserver123"

},

...

}

and then we use that instead of the hard-coded values throughout our code. Like this

{

...

"resources": [

{

"name": "[variables('sqlServerName')]",

...

"resources": [

{

...

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', variables('sqlServerName'))]"

],

...

},

{

...

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', variables('sqlServerName'))]"

]

}

]

}

],

"outputs": {}

}

That is much cleaner! And much easier to update!

Resources as cattle, not as pets

A common saying in the IaC world is “treat your resources as cattle, not pets”. This means that we don’t want “snowflake” resources that you name, care for and get a relationship to. Like a pet. Instead you want cattle. Resources that are automatically set up, named using some form of standard, and that can be replaced whenever it misbehaves.

One of the big things with this saying, is the naming part. Naming things with “proper” names, indicates that it is a pet, not cattle. This causes a bunch of issues. Including things like resource names already being in use etc.

By adding a random suffix to your resource names, you get away from this “pet situation”, and actually simplify a lot of things.

Note: But what about connection string and other references used by application? How does that cope with randomly naming resources? Well, all of that configuration should be automated as well, so that it uses the generated names… But that is a whole other topic!

To make out naming a bit more “cattle like”, we can update the sqlServerName variable like this

{

...

"variables": {

"namingSuffix": "[uniqueString(resourceGroup().id)]",

"sqlServerName": "[concat('mydemosqlserver123', variables('namingSuffix'))]"

},

...

}

This generates a new namingSuffix variable that uses the uniqueString() function to generate a string value that is calculated based on the ID of the current resource group. This means that you get a string that is unique for your specific resource group.

Note: Naming is obviously very important, since it is used by the resource manager to figure out if it needs to update or create a resource. Because of this, we want a “random” name, that is still going to be stable for our specific deployment. That’s why we generate a name based on the Resource Group ID and not just a random string, as a random string would change for every deployment.

We then use the concat() function to add it to the end of the sqlServerName variable. This will give use a name that is going to be unique for the chosen Resource Group.

Sweet! This makes it much less likely that the deployment will fail due to a duplicate resource names.

Adding the Log Analytics Workspace

The next step is to add the Log Analytics Workspace that we are going to use to store the telemetry created by Application Insights.

Once again, this is just a matter of adding another JSON resource block that looks like this

{

...

"resources": [

...

{

"name": "[concat('MyDemoWorkspace', variables('namingSuffix'))]",

"type": "Microsoft.OperationalInsights/workspaces",

"apiVersion": "2021-06-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"properties": {

"sku": {

"name": "Free"

}

}

}

],

...

}

That’s it! However, I’m feeling like there is even more of a naming convention at play here… I’m prefixing each of my names with MyDemo. Maybe we can use another variable to sort that out…

{

...

"variables": {

"projectName": "MyDemo",

"namingSuffix": "[uniqueString(resourceGroup().id)]",

"sqlServerName": "[concat(toLower(variables('projectName')), '-sql-', variables('namingSuffix'))]"

},

"resources": [

...

{

"name": "[concat(variables('projectName'), '-ws-', variables('namingSuffix'))]",

...

}

]

...

}

Awesome! That gives us even more or a “cattle” naming standard. It generates the resource name by combining the “project name”, the resource type (hyphenated) and the suffix. This generates automated names, while keeping the readability.

Note: For this simple scenario, I’m using a very simple naming strategy. In a real environment, I would suggest finding a naming strategy that includes some form of resource identifier/project name, the type of resource, maybe the location depending on the distribution of the app, maybe a number in case you need multiple instances, and finally a “random” suffix. For example something like “mydemo-sql-weu-01-xxxxxx”. It’s up to you to find a naming strategy that works for you, but a thought through strategy is generally very nice to have.

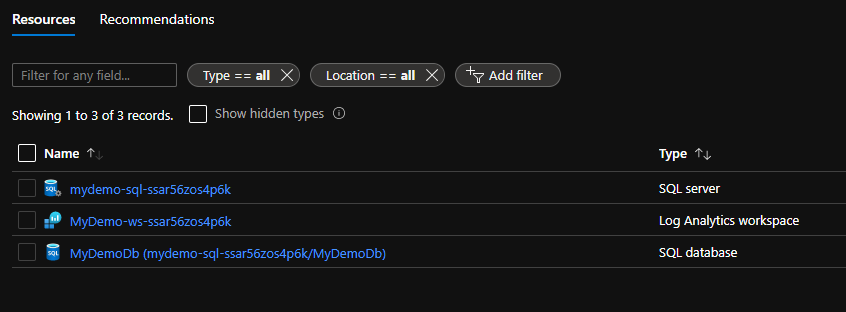

Deploying the template in its current state in my subscription, ended up creating this

But we can actually make naming resources even cooler if we want to…

User-defined functions

We managed to refactor away the repetitive use of the SQL Server name, however, we are now repetitively generating resource names that are actually based on a standard. Doing this manually can be a bit error prone, so why not automate it?

This is where user-defined functions come into play. They allow us to create our own functions that can be used to get away from repetitive code. In our case, we want a function that can concatenate a couple of string in a standardized way, and return the result. It could look something like this

{

...

"functions": [

{

"namespace": "demo",

"members": {

"resourceName": {

"parameters": [

{ "name": "projectName", "type": "string" },

{ "name": "resourceType", "type": "string" },

{ "name": "toLower", "type": "bool" }

],

"output": {

"type": "string",

"value": "[if(parameters('toLower'),

toLower(concat(parameters('projectName'), '-', parameters('resourceType'), '-', uniqueString(resourceGroup().id))),

concat(parameters('projectName'), '-', parameters('resourceType'), '-', uniqueString(resourceGroup().id))

)]"

}

}

}

}

],

...

}

As you can see, this uses the functions section to declare a new function namespace called demo, containing a single function called resourceName. The resourceName function takes 3 parameters, and returns (outputs) a properly concatenated resource name.

Note: The use of namespaces for the functions allows us not only to group functions in different ways. It also makes it less likely to cause naming collisions.

Creating a user-defined function isn’t hard, but it does takes a little time to get used to writing functions in JSON. Luckily, the actual functionality is often easy to create, as ARM includes quite a few of the logical constructs you might be needing. For example if(), false() and true(). But it is still very limited compared to a real coding language…

One limitation when it comes to functions, is that they cannot reference variables. This means that the uniqueString() call needs to be moved inside the function. Making it possible to remove the namingSuffix.

Another option would be to pass in the naming suffix as a parameter in every call. But I find moving the call to uniqueString() inside the function to be cleaner. And since the return value from that call is “scoped” to the current resource group, and not random, the end result is identical.

To use the function, we can update our template like this

{

...

"variables": {

"projectName": "MyDemo",

"sqlserverName": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'sql', true())]"

},

"resources": [

...

{

"name": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ws', false())]",

...

}

],

...

}

Sure, it doesn’t make a huge difference for a simple template like this. But in a bigger scenario it can make the JSON a lot easier to read, and less prone to errors.

Creating the Web App

Now that the pre-requisites are up and running, I guess it is time to go into the nitty gritty of setting up the App Service Plan and the App Service. Luckily, once again it is just a matter of adding a couple of resources.

For the App Service Plan, it looks like this

{

...

"resources": [

...

{

"name": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'plan', false())]",

"type": "Microsoft.Web/serverfarms",

"apiVersion": "2021-01-15",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"sku": {

"name": "F1",

"capacity": 1

},

"properties": {}

}

],

...

}

Fairly basic! Not sure why the empty properties element has to be there. But without it, the VS Code extension complains. So I’m leaving it in there to silence it…

The Web App looks like this

{

...

"resources": [

...

{

"name": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false())]",

"type": "Microsoft.Web/sites",

"apiVersion": "2021-01-15",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"properties": {

"serverFarmId": "[resourceId('Microsoft.Web/serverfarms', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'plan', false()))]",

"siteConfig": {

"netFrameworkVersion": "v5.0",

"connectionStrings": [

{

"name": "connectionstring",

"connectionString": "[format('Data Source=tcp:{0},1433;Initial Catalog={1};User Id={2};Password={3};',

reference(resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', variables('sqlserverName'))).fullyQualifiedDomainName,

'MyDemoDb',

'server_admin',

'P@ssw0rd1!'

)]",

"type": "SQLAzure"

}

]

}

},

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', variables('sqlServerName'))]"

]

},

],

...

}

This is a bit more complicated as it requires a server farm ID, a NET Framework configuration, a connection string to the database and a dependsOn. But all in all, it should be pretty readable by now I think.

It is worth noting that I am hard coding the database credentials at the moment, which I definitely do not think you should. But it will have to do for now, as it is simpler to read. I will remove the hard coded values in a little while.

Warning: Do not check in a template with credentials in it to source control at any point. Even if you remove the credentials later on, it will still be possible to pull out the old version and see the credentials!

We are currently missing the app settings for Application Insights, which is a problem. On the other hand, we don’t have an Application Insights resource yet either… However, since the AI resource needs a reference to the Web App, it becomes a bit of a catch 22. But don’t worry, we’ll sort it all out in a few minutes.

Setting upp Application Insights

Now that we have the Web App and Log Analytics Workspace resources, we can go ahead and add the Application Insights resource. This is once again done by adding yet another resource block that looks like this

{

...

"resources": [

...

{

"type": "Microsoft.Insights/components",

"apiVersion": "2020-02-02",

"name": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ai', false())]",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"tags": {

"[format('hidden-link:{0}', resourceId('Microsoft.Web/sites', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false())))]": "Resource",

},

"kind": "web",

"properties": {

"Application_Type": "web",

"WorkspaceResourceId": "[resourceId('Microsoft.OperationalInsights/workspaces', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ws', false()))]"

},

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Web/sites', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false()))]"

]

}

],

...

}

As you can see, it is just a resource like all the others. There is just one slightly odd thing in here to be honest, and that is the hidden-link tag that is being set up. First of all…why? Well, it has to do with some internal stuff for Azure, so let’s just say it apparently should be there. And secondly…what the heck kind of syntax is that? Well, it uses the format() function to create a string that looks like this "hidden-link:<WEB APP RESOURCE ID>": "Resource". This is perfectly valid JSON, even if the property name includes a :. However, it is hard to write in the template as it needs the resource ID in the property name. But since the ARM functions are evaluated before the JSON is read, we can use the format() function to generate the JSON we need. It just looks really wonky…

The last part of this puzzle is the need to set up a couple of App Settings in the Web App. But as I just mentioned, the Application Insights resource needs the Web App to exist to be able to set the hidden-link tag. And the Web App needs the Application Insights resource to exist to be able to set the required Web App configuration… A bit of a catch 22…

Luckily, we can actually break out the Web App configuration into a separate resource that looks like this

{

...

"resources": [

...

{

"type": "Microsoft.Web/sites/config",

"apiVersion": "2021-01-15",

"name": "[format('{0}/{1}', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false()), 'web')]",

"properties": {

"appSettings": [

{

"name": "APPINSIGHTS_INSTRUMENTATIONKEY",

"value": "[reference(resourceId('Microsoft.Insights/components', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ai', false()))).InstrumentationKey]"

},

{ "name": "ApplicationInsightsAgent_EXTENSION_VERSION", "value": "~2" },

{ "name": "XDT_MicrosoftApplicationInsights_Mode", "value": "recommended" }

]

},

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Web/sites', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false()))]",

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Insights/components', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ai', false()))]"

]

}

],

...

}

So, instead of setting all of the application configuration under the Web App resource, we break out that specific part of the resource configuration. This is a bit more advanced than just your run of the mill resource, but it isn’t really that different to setting up any other resource. The biggest thing here is that the name is now back to that 2 part version that I was talking about at the beginning. In this case, the name becomes <WEB APP NAME>/web, which is achieved by using the format() function. Other than that, it is just a matter of setting the appSetttings array to the required settings.

That’s actually the whole thing. This should set up all the infrastructure that we need to run our application. However…there is still some stuff that can be made better.

Adding Parameters

One thing that we added at the end of the previous post, was the use of input parameters. This is just as valid in this case. Right now, we have a few hard coded values that would be nice to make into input parameters instead.

This is obviously where the parameters section comes into play! In this section, we can define not only what parameters we need, but also default values, allowed values and meta data that can be used to ask the user for the input in a more human readable format.

Note: You can add as many input parameters as you want, depending on how flexible you want the template to be. In this case, I’m sticking with the same parameters I used in the last post.

So, let’s go ahead and add the same parameters as we did in the last post, except for the location, as this will be defined by the Resource Group that the template is being deployed to

{

...

"parameters": {

"appName": {

"type": "string",

"metadata": {

"description": "The name of the application"

}

},

"sqlSize": {

"type": "string",

"defaultValue": "S0",

"allowedValues": [

"Basic",

"S0",

"S1",

"S2",

"P1",

"P2"

],

"metadata": {

"description": "The SQL Server database size"

}

},

"sqlUser": {

"type": "string",

"defaultValue": "server_admin",

"metadata": {

"description": "SQL Admin username"

}

},

"sqlPwd": {

"type": "securestring",

"metadata": {

"description": "SQL Admin password"

}

},

"appSvcPlanSku": {

"type": "string",

"defaultValue": "F1",

"allowedValues": [

"F1",

"B1",

"B2",

"S1",

"S2",

"P1",

"P2"

],

"metadata": {

"description": "The service plan size"

}

}

},

...

}

As you can see, this just defines the input parameters for the template as properties on the parameters object. Each containing at least a name and a type, but with the option to add default values etc.

If they have the defaultValue property set, they are not required to be passed in. If a default value isn’t provided, you will be prompted for the value unless you provide it during deployment.

I also made sure to set the sqlPwd to be of type securestring. This makes sure that the value is treated in a secure way, and that it isn’t available to be read after the deployment. This is definitely recommended when using parameters passwords and the like.

These values can then be used instead of the hard coded values throughout the template by using [parameters('<PARAMETER NAME>')].

After having updated all the hard coded values with the parameters, the template looks like this

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentTemplate.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"parameters": {

"appName": {

"type": "string",

"metadata": {

"description": "The name of the application"

}

},

"sqlSize": {

"type": "string",

"defaultValue": "S0",

"allowedValues": [

"Basic",

"S0",

"S1",

"S2",

"P1",

"P2"

],

"metadata": {

"description": "The SQL Server database size"

}

},

"sqlUser": {

"type": "string",

"defaultValue": "server_admin",

"metadata": {

"description": "SQL Admin username"

}

},

"sqlPwd": {

"type": "securestring",

"metadata": {

"description": "SQL Admin password"

}

},

"appSvcPlanSku": {

"type": "string",

"defaultValue": "F1",

"allowedValues": [

"F1",

"B1",

"B2",

"S1",

"S2",

"P1",

"P2"

],

"metadata": {

"description": "The service plan size"

}

}

},

"functions": [

{

"namespace": "demo",

"members": {

"resourceName": {

"parameters": [

{ "name": "projectName", "type": "string" },

{ "name": "resourceType", "type": "string" },

{ "name": "toLower", "type": "bool" }

],

"output": {

"type": "string",

"value": "[if(parameters('toLower'),

toLower(concat(parameters('projectName'), '-', parameters('resourceType'), '-', uniqueString(resourceGroup().id))),

concat(parameters('projectName'), '-', parameters('resourceType'), '-', uniqueString(resourceGroup().id))

)]"

}

}

}

}

],

"variables": {

"projectName": "[parameters('appName')]",

"sqlserverName": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'sql', true())]"

},

"resources": [

{

"name": "[variables('sqlserverName')]",

"type": "Microsoft.Sql/servers",

"apiVersion": "2014-04-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"properties": {

"administratorLogin": "[parameters('sqlUser')]",

"administratorLoginPassword": "[parameters('sqlPwd')]"

},

"resources": [

{

"name": "MyDemoDb",

"type": "databases",

"apiVersion": "2014-04-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', variables('sqlServerName'))]"

],

"properties": {

"collation": "SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS",

"requestedServiceObjectiveName": "[parameters('sqlSize')]"

}

},

{

"type": "firewallRules",

"apiVersion": "2021-02-01-preview",

"name": "AllowAllWindowsAzureIps",

"properties": {

"endIpAddress": "0.0.0.0",

"startIpAddress": "0.0.0.0"

},

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', variables('sqlServerName'))]"

]

}

]

},

{

"name": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ws', false())]",

"type": "Microsoft.OperationalInsights/workspaces",

"apiVersion": "2015-11-01-preview",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"properties": {

"sku": {

"name": "Free"

}

}

},

{

"name": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'plan', false())]",

"type": "Microsoft.Web/serverfarms",

"apiVersion": "2018-02-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"sku": {

"name": "[parameters('appSvcPlanSku')]",

"capacity": 1

},

"properties": {}

},

{

"name": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false())]",

"type": "Microsoft.Web/sites",

"apiVersion": "2018-11-01",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Web/serverfarms', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'plan', false()))]",

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', variables('sqlServerName'))]"

],

"properties": {

"siteConfig": {

"netFrameworkVersion": "v5.0",

"connectionStrings": [

{

"name": "connectionstring",

"connectionString": "[format('Data Source=tcp:{0},1433;Initial Catalog={1};User Id={2};Password={3};',

reference(resourceId('Microsoft.Sql/servers', variables('sqlserverName'))).fullyQualifiedDomainName,

'MyDemoDb',

parameters('sqlUser'),

parameters('sqlPwd')

)]",

"type": "SQLAzure"

}

]

}

}

},

{

"type": "Microsoft.Insights/components",

"apiVersion": "2020-02-02",

"name": "[demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ai', false())]",

"location": "[resourceGroup().location]",

"kind": "web",

"properties": {

"Application_Type": "web",

"WorkspaceResourceId": "[resourceId('Microsoft.OperationalInsights/workspaces', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ws', false()))]"

},

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Web/sites', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false()))]"

]

},

{

"type": "Microsoft.Web/sites/config",

"apiVersion": "2020-12-01",

"name": "[format('{0}/{1}', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false()), 'web')]",

"properties": {

"appSettings": [

{

"name": "APPINSIGHTS_INSTRUMENTATIONKEY",

"value": "[reference(resourceId('Microsoft.Insights/components', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ai', false()))).InstrumentationKey]"

},

{ "name": "ApplicationInsightsAgent_EXTENSION_VERSION", "value": "~2" },

{ "name": "XDT_MicrosoftApplicationInsights_Mode", "value": "recommended" }

]

},

"dependsOn": [

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Web/sites', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false()))]",

"[resourceId('Microsoft.Insights/components', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'ai', false()))]"

]

}

],

"outputs": {}

}

Yes, that is a lot of text, but if you take it step by step, it is mostly pretty readable. And it is only about 200 lines, compared to the 1600+ lines used by the exported templates I talked about at the beginning of the post!

Deploying with parameters

Now that we have added the parameters, if you try to deploy the template using the following command

> az deployment group create -g MyDemoGroup -n MyDemo --template-file iac.json

You will be faced with an input prompt asking for values for the 2 parameters that do not have defaults.

If you are running in a build pipeline for example, an interactive prompt like this would be a very bad idea. To fix that, you can pass the parameter values to the az deployment group create command using the --parameters parameter like this

> az deployment group create `

-g MyDemoGroup `

-n MyDemo `

--template-file iac.json `

--parameters appName='MyDemo' sqlPwd='P@ssword1!'

However, if you have a lot of parameters, it is probably easier to use a parameters file.

And “what is a parameters file?” you ask. Well, it is basically just the input values for the parameters defined in a separate JSON file like this

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentParameters.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"parameters": {

"appName": { "value": "MyDemo" },

"sqlPwd": { "value": "P@ssword1!" }

}

}

Yes, having to do an object literal with a value property for each value is a bit of a pain, but that’s just the way it is…

This file can then be passed to the Azure CLI command during deployment by adding the same --parameters parameter, but setting the value to path to the parameters file. Like this

> az deployment group create `

-g MyDemoGroup `

-n MyDemo `

--template-file iac.json `

--parameters ./parameters.json

However, once again we are hard coding credentials… Even if it is inside a parameters file, it is probably not the best solution. To get away from that, we can remove the SQL password from the parameters file, and pass that specific value to the command as a separate input. All we have to do, is to add 2 --parameter parameters. Like this

> az deployment group create `

-g MyDemoGroup `

-n MyDemo `

--template-file iac.json `

--parameters ./parameters.json `

--parameters sqlPwd='P@ssword1!'

And for the love of all that means something, do not use P@ssword1! as your password!!!

Outputs

The last section, outputs, allows us to output selected values from the deployment. These values can then be retrieved using the Azure CLI for example, based on the specific Resource Group and deployment name. This can be very helpful in a deployment pipeline that sets up dynamically named resources for example.

Say that we for example needed to get the address to the Web App we just set up, so that we could use it in later step of our deployment pipeline. This information could then be added as an output like this

{

"outputs": {

"websiteAddress": {

"type": "string",

"value": "[format('https://{0}/', reference(resourceId('Microsoft.Web/sites', demo.resourceName(variables('projectName'), 'app', false()))).defaultHostName)]"

}

}

}

Yeah, there is a bit of formatting going on here as the Web Apps resource’s defaultHostName property only contains the actual host name. So, to get a proper URL, we format it by prefixing it with http://, and adding a / at the end for good measure.

This value can then be retrieved together with all the information about the deployment using the Azure CLI. All we need to do is to call az deployment group show, passing in the Resource Group name, and deployment name. Like this

> az deployment group show `

-g MyDemoGroup `

-n MyDemo

{

"id": "/subscriptions/ba40d97f-a1a4-4a24-9f9b-f0d70b447d1f/resourceGroups/MyDemoGroup/providers/Microsoft.Resources/deployments/MyDemo",

"location": null,

"name": "MyDemo",

...

}

However, that returns a lot of info. All the information to be honest! If you just want that specific value, you can use the --query parameter like this

> az deployment group show `

-g MyDemoGroup `

-n MyDemo `

--query properties.outputs.websiteAddress.value `

-o tsv

https://mydemo-app-ssar56zos4p6k.azurewebsites.net/

Using output values can, as I said before, be a really useful way to provide a deployment pipeline information about the deployed infrastructure. Something that is very likely to be needed when you start adopting IaC in your CD pipelines.

I think that pretty much covers ARM templates from a high level! This template should offer us the same features as the PowerShell script from the previous post, but with the added benefit of it being declarative. This allows us to focus on the desired state of the infrastructure we need, and the Azure Resource Manager does the rest!

Note: Don’t forget to clean up the resources once you are done playing with the ARM template! (az group delete -n MyDemoGroup -y)

Conclusion

I am, as mentioned before, not a huge fan of ARM templates. I find them to be a bit verbose, and I dislike the need for the API versions in the definition, even if I know that they are there for a reason. As a developer, I also find declarative DSL:s to be a bit limiting when it comes to what you can actually do. However, that is not ARM template specific. I find pretty much the same limitations when it comes to for example Terraform.

Having that said, ARM templates do have very good documentation, and there is a lot of knowledge around the topic in the community, so finding out how to do things, or solutions to issues, is pretty simple. This is definitely a major plus for ARM compared to some of the alternatives.

It is also a native solution for Azure. This means that pretty much anything that can be set up in Azure, can be set up using ARM templates. There is no need to wait for the community to update the tool you work with before you can start using new features. This tends to be a common problem when using some of the other tools.

It is also quite obvious that Microsoft has heard the feedback about the ARM templates being verbose and cumbersome to work with. Their response to this, is a new way to create ARM-based templates called Bicep, which I cover in this follow up post - Infrastructure as Code - An intro - Part 4 - Using Bicep